Sarcopenia and Resting Energy Expenditure After 50

Understanding age-related muscle mass loss and metabolic implications in midlife women

The Primary Driver: Lean Tissue Loss

Sarcopenia—the progressive decline in skeletal muscle mass and strength with advancing age—is the single most significant driver of reduced resting energy expenditure (REE) in women after age 50. This relationship is direct and mechanistic: lean tissue is metabolically active tissue. Muscle at rest requires ongoing ATP production, protein turnover, and ion gradient maintenance, consuming energy continuously. Conversely, adipose tissue—body fat—is comparatively metabolically inert, requiring approximately 2–3 times less energy per unit mass than muscle.

Cross-sectional studies demonstrate that resting metabolic rate correlates strongly with lean body mass across age groups. Longitudinal research tracking women over decades reveals that the rate of REE decline closely parallels the rate of lean mass loss, supporting a causal relationship rather than coincidental association.

Mechanisms of Age-Related Muscle Loss

Sarcopenia develops through multiple overlapping mechanisms:

- Reduced protein synthesis: Aging muscle shows blunted responses to amino acid availability and resistance training stimulus, requiring higher amino acid thresholds to trigger muscle protein synthesis.

- Mitochondrial dysfunction: Age-related decline in mitochondrial number and efficiency reduces ATP production capacity and increases oxidative stress in muscle.

- Neuromuscular changes: Loss of motor neurons and reduced neuromuscular junction efficiency contribute to decreased muscle fibre recruitment and strength.

- Hormonal shifts: Declines in growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and other anabolic hormones reduce signals for muscle maintenance and growth.

- Inflammatory environment: Increased systemic inflammation (sometimes termed "inflammaging") creates a catabolic environment unfavourable to muscle preservation.

- Physical inactivity: Reduced activity—both structured exercise and spontaneous movement—accelerates disuse atrophy and reduces muscle stimulation.

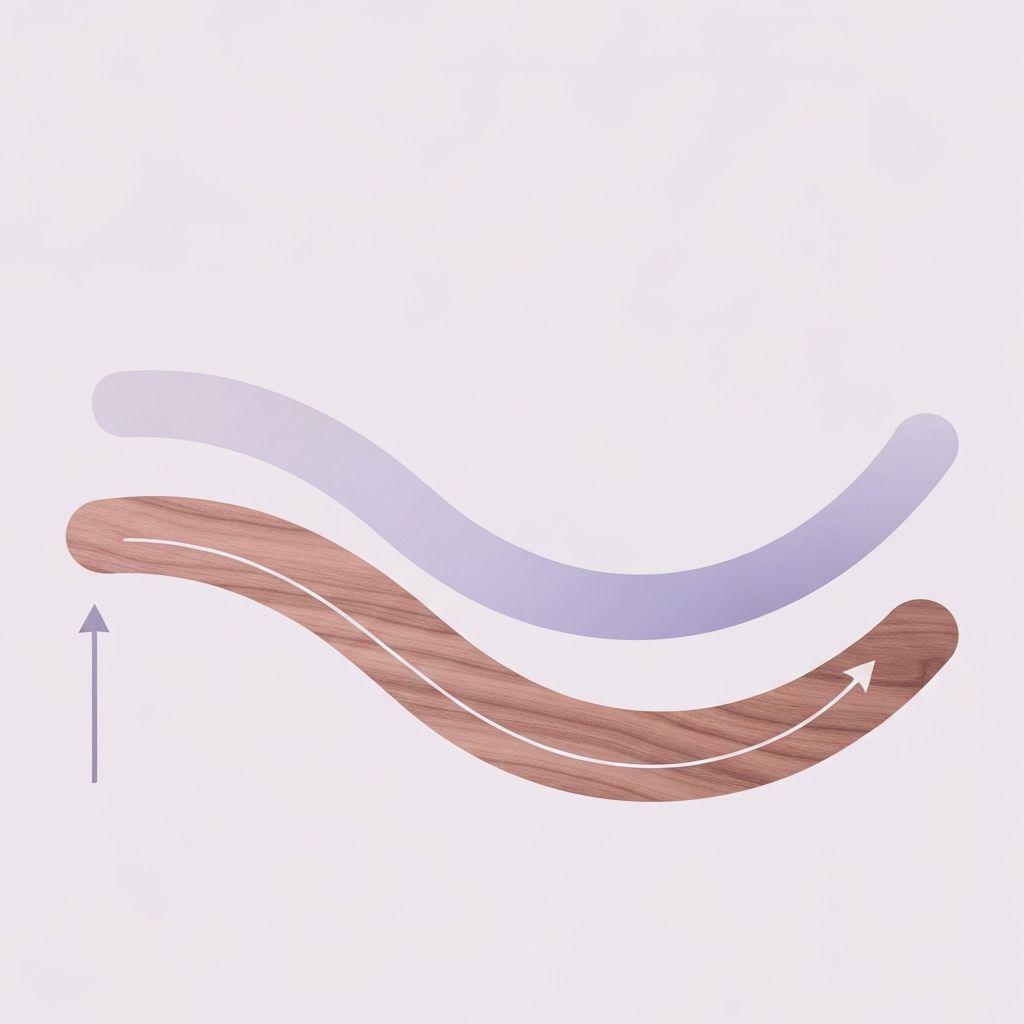

These mechanisms interact and compound. A woman who becomes less active experiences reduced stimulus for muscle protein synthesis, which may further reduce motivation for activity, creating a downward spiral in lean mass retention.

Quantifying the Loss

Research data on the magnitude of sarcopenia in midlife women:

| Age Range | Average Annual Lean Mass Loss (%) | Approximate REE Impact | Study Population Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20–30 years | ~0.3–0.5% | Minimal (~10–15 kcal/day per year) | Largely activity-dependent; high variability |

| 40–50 years | ~0.5–0.8% | ~15–25 kcal/day per year | Acceleration begins; hormonal influence emerging |

| 50–60 years | ~0.8–1.2% | ~20–35 kcal/day per year | Menopause influence; activity transitions |

| 60+ years | ~1.0–1.5% | ~25–45 kcal/day per year (cumulative) | Accelerated loss; highly individual variation |

Over a 10-year period from age 50 to 60, a woman losing lean mass at 1% annually would experience a cumulative lean mass reduction of approximately 9.5% (accounting for compounding). If lean mass comprised 35% of body weight at age 50 in a 65 kg woman (~22.75 kg), this represents a loss of ~2.2 kg of muscle—directly reducing REE by roughly 150–200 kcal/day or more, depending on individual mitochondrial density and muscle fibre composition.

Individual Variability

Critical to note: sarcopenia rates vary significantly among individuals. Women who maintain regular resistance training often experience muscle loss rates in the lower range (0.3–0.5% annually), while sedentary women may lose 1.5% or more annually. Genetic predisposition, hormonal environment, nutritional adequacy, and overall health status all influence the trajectory.

Longitudinal studies tracking diverse cohorts of women through midlife show that muscle loss is neither inevitable nor uniform. Those maintaining physical activity and adequate protein intake sustain substantially higher lean mass into older age, though the age-related decline itself—the biological process—occurs universally.

Implications for Energy Balance

The reduction in REE due to sarcopenia is one component of broader energy balance shifts in midlife. A woman whose REE declines by 200 kcal/day due to muscle loss experiences a shift in her daily energy balance equation. To maintain the same body weight, she would require proportionally reduced energy intake or increased activity. This does not reflect metabolic dysfunction but rather a natural physiological consequence of altered body composition.

Understanding this mechanism contextualises why some women observe that "eating the same as I did at 40" results in weight gain at 55—not because metabolism has "broken," but because the metabolic cost of maintaining her body has decreased due to compositional changes. Recognition of this distinction enables informed decision-making about energy balance without invoking mystery or pathology.