Overview of Metabolic Changes After 50

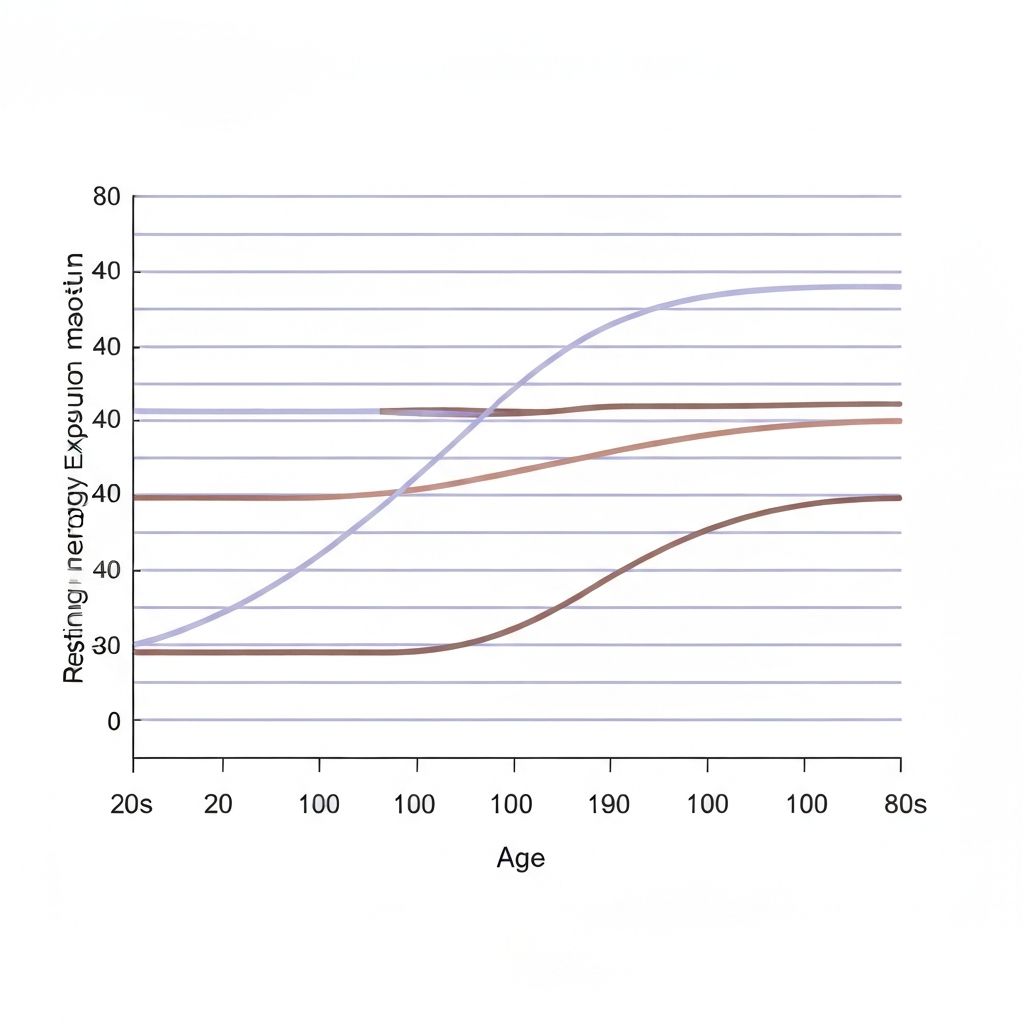

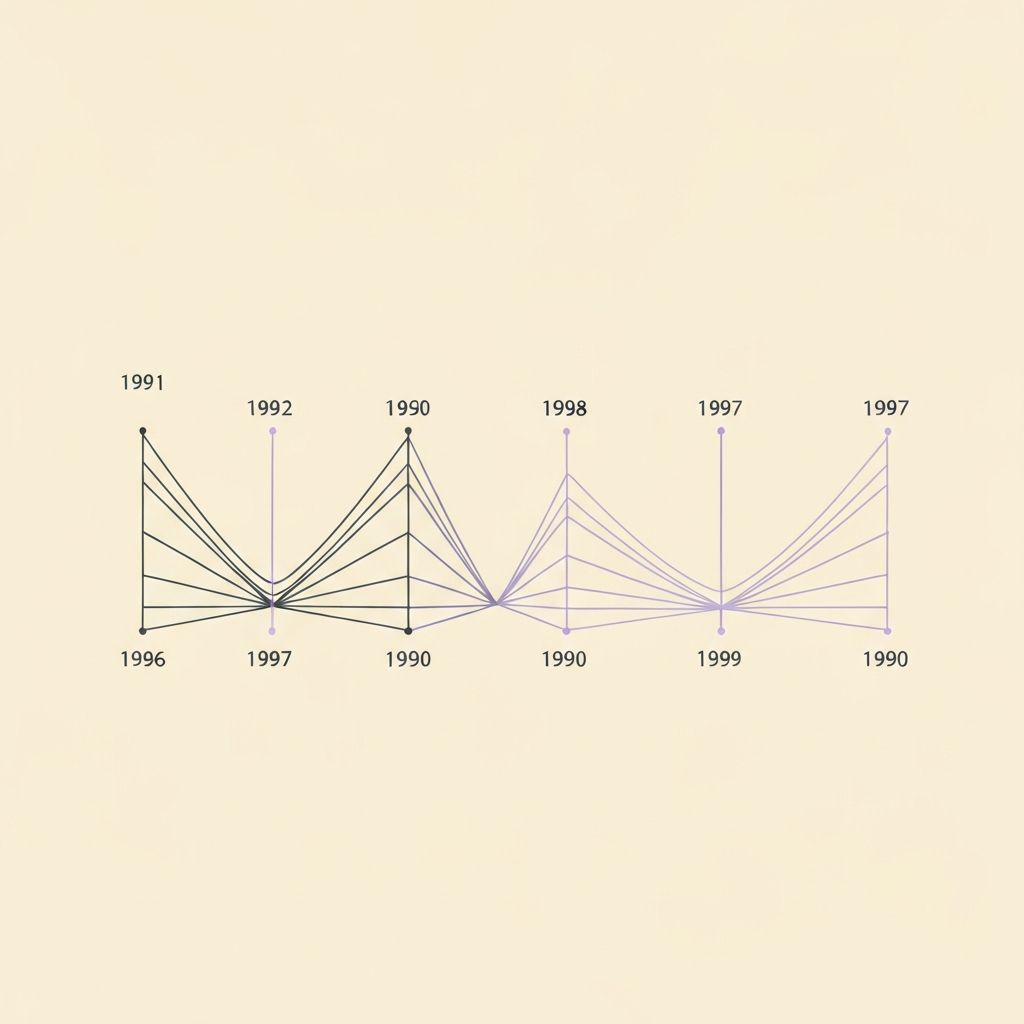

Resting energy expenditure (REE) demonstrates a general decline across the adult lifespan, with research indicating approximately 1–2% decrease per decade after age 20. This reduction becomes more pronounced in women after age 50, driven primarily by changes in body composition and hormonal dynamics during the menopausal transition.

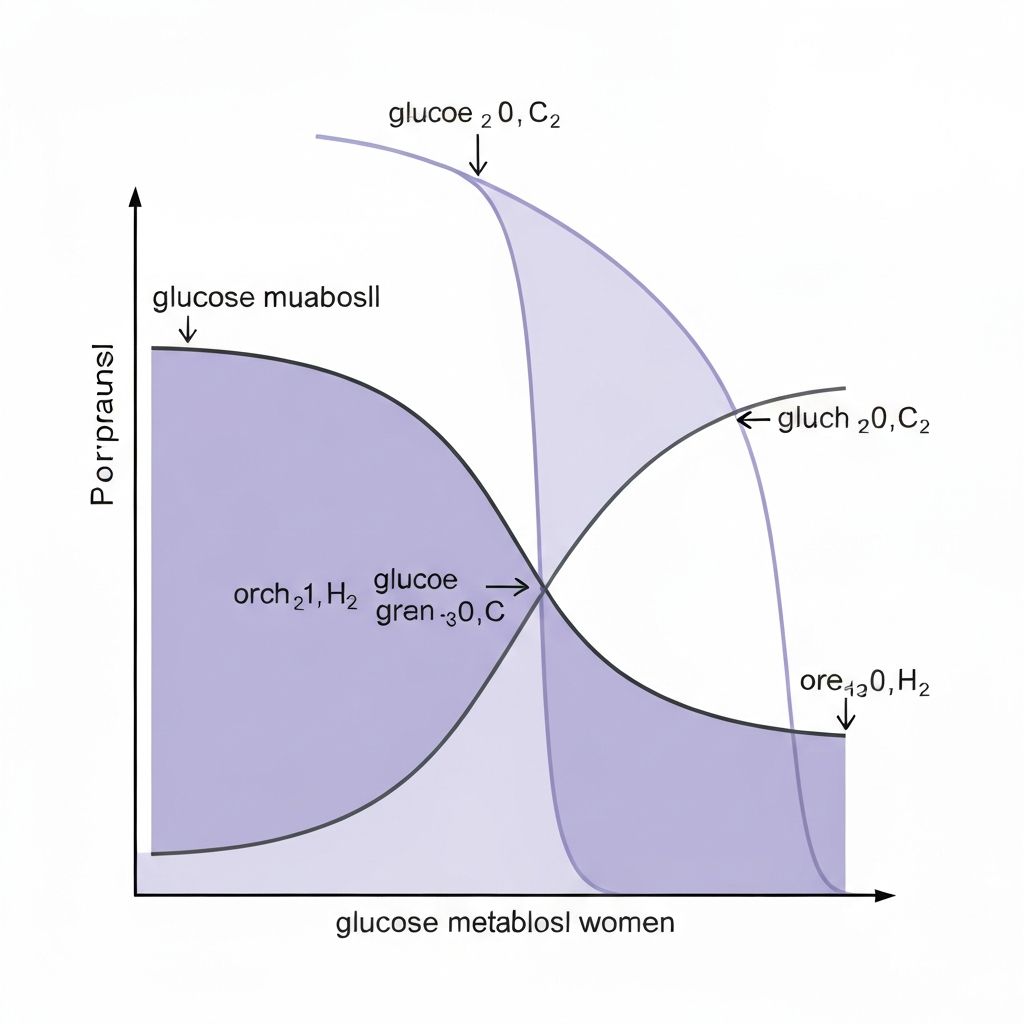

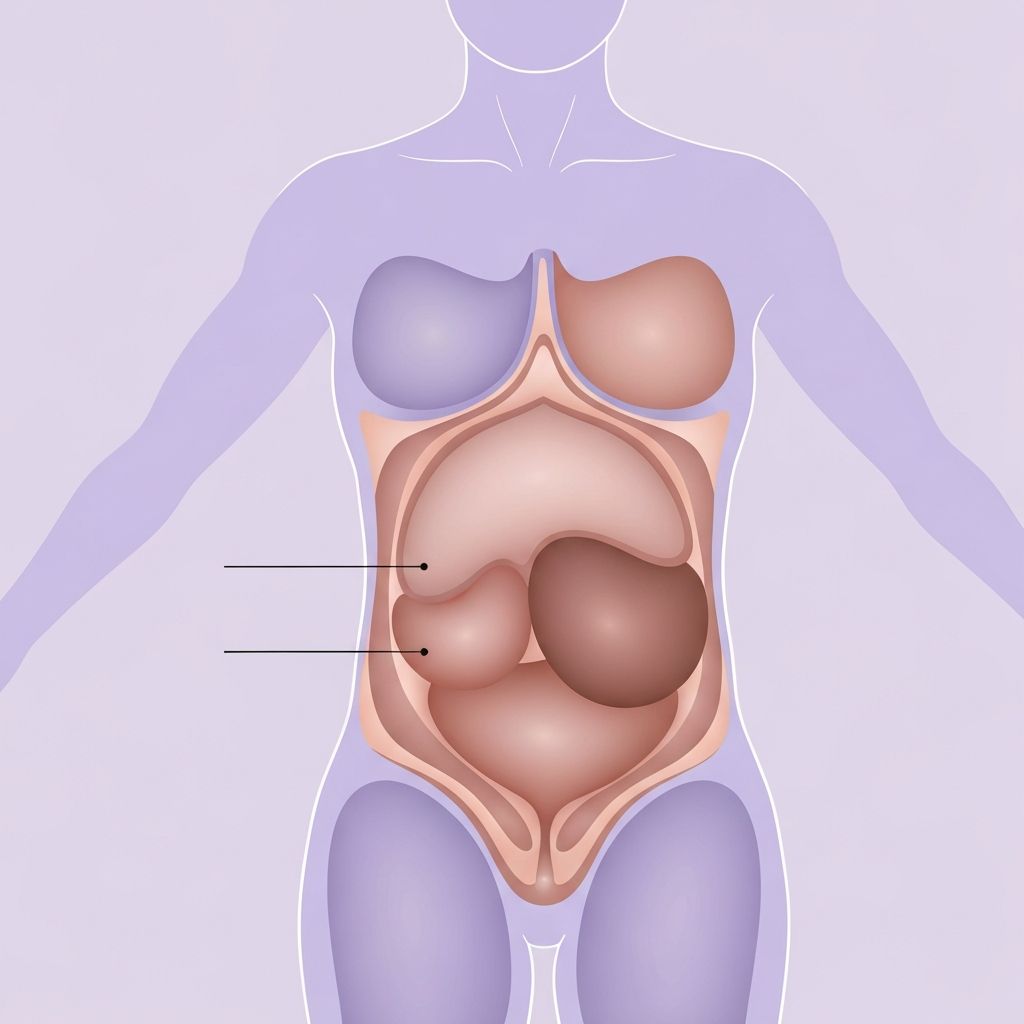

The average woman experiences shifts in total energy expenditure due to multiple interconnected factors: loss of lean muscle tissue, redistribution of adipose tissue, alterations in spontaneous activity levels, and hormonal fluctuations. These changes are gradual and multifactorial rather than sudden metabolic collapse.

Understanding these physiological shifts provides context for why energy balance patterns change in midlife without requiring personalised dietary or exercise interventions.